‘From rebel to national treasure’: How Paul O’Grady won our hearts with his drag alter ego Lily Savage

A year on from O’Grady’s death, an ITV documentary charts the rise of the comedian’s drag persona, and lifts the lid on the kind man behind the cutting character. Katie Rosseinsky talks to the director and O’Grady’s close friend, Gaby Roslin

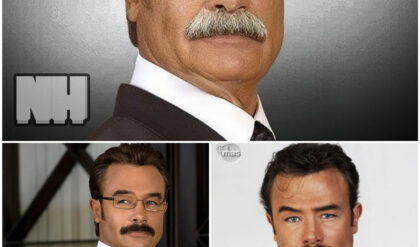

Subversive: a new documentary celebrates O’Grady’s drag persona (ITV/iStock/Getty)

On a Saturday night in January 1987, Paul O’Grady was on stage at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. He was performing as his drag alter ego Lily Savage, the Scouse sex worker with an acid tongue and a towering blonde wig.

Then the police burst in: the raid was ostensibly part of a crackdown on amyl nitrate, or poppers, but was also seen as an attempt to intimidate the gay community. Aids panic was at its height, and the officers all wore rubber gloves to avoid touching the crowd. “It looks like we’ve got help with the washing up,” O’Grady quipped.

There are few showbiz careers that manage to encompass an arrest at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern and heartwarming teatime TV shows about rescue dogs. But Paul O’Grady, who gave his “real name” to the desk sergeant at the police station that night as “Lily Veronica Mae Savage”, did just that – and never lost his subversive edge.

A year on from O’Grady’s death at the age of 67, ITV’s new documentary The Life and Death of Lily Savage charts how his drag persona emerged against the backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, Section 28 (the notorious legislation banning local authorities from “the promotion of homosexuality”) and the Aids crisis.

It then explores how Lily took on the mainstream – before O’Grady eventually retired his character at the height of her popularity, only to forge an entertainment career in his own right. “The story is from rebel to national treasure, really,” says Sam Anthony, the documentary’s director. “That’s quite a journey, and it didn’t take him that long to do.”

O’Grady was “a great talker”, the director notes, so Anthony wanted to find a way for his words, and wit, to form the backbone of the documentary. Although O’Grady released four different autobiographies, he never recorded audio versions, meaning that Anthony had to embark on “a bit of a detective mission”.

“I basically tried to find every single interview he’d ever done, podcasts, news interviews, stuff like that, and then tried to build a structure out of the things that he actually said himself,” he explains.

The documentary begins in Birkenhead on the Wirral, where O’Grady was born in 1955, to “very Catholic” parents. From a young age, he was drawn to the “excitement” of Liverpool, the city he’d see from across the river Mersey. “As a child, it was my personal little Camelot, nothing else existed,” we hear him explain in the film.

The spirited women he grew up with would eventually provide him with inspiration for Lily, not least his Auntie Chrissie, a glamorous bus conductor with a no-messing attitude (“She came across as quite hard-bitten, but […] she was daft as a brush,” he later told Desert Island Discs). “He genuinely loved working-class women,” Anthony says. “He loved women of a certain age, ‘difficult women’.”

When O’Grady eventually moved to London in his twenties, he worked as a “peripatetic care officer” (or, as he put it, a “bizarre Mary Poppins”) for Camden Council: “If a single mother had to go to hospital, I’d move in and look after her kids so they didn’t have to go into care,” he later recalled to The Independent.

It was an experience that “helped with his sense of social justice”, Anthony says. He saw the impact of cuts to social care first hand, and never forgot it: see his barnstorming speech on Paul O’Grady Live in 2010, when he ripped into the Tory government’s austerity budget. “Bastards,” he hissed, presumably giving his producers an anxiety attack in the process.

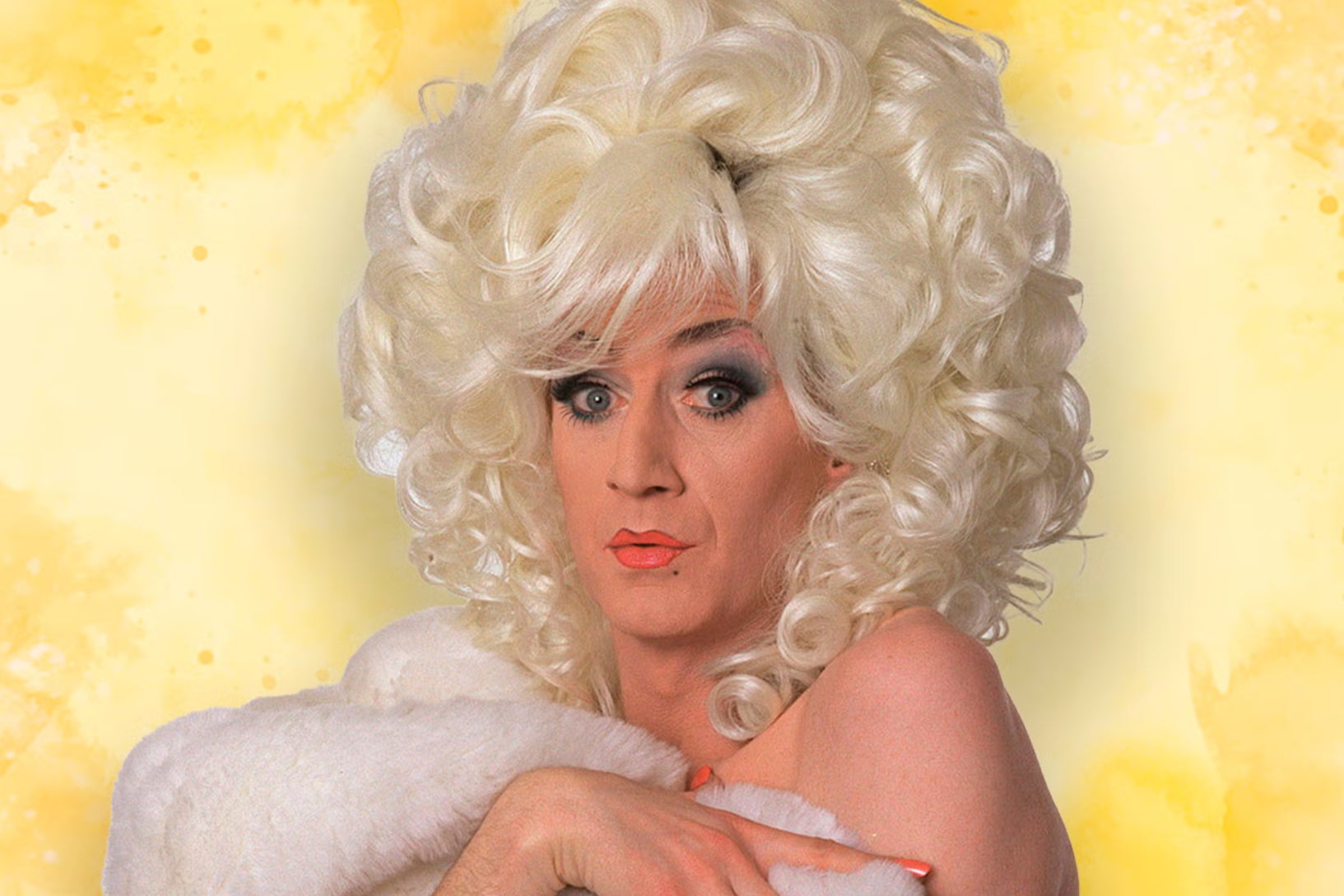

Alter ego: O’Grady in character as Lily Savage, complete with trademark blonde wig (PA)

Around the same time as working for the council, he made his debut as Lily Savage at The Black Cap, Camden’s legendary gay pub. The character seemed to emerge almost fully formed (no surprise, given that O’Grady had been making his friends laugh with his impressions of Scouse housewives for years).

Instead of opting for all-out, OTT glamour, Lily had “her roots showing and a rip in her tights”, we hear O’Grady recall.

Care worker by day, drag queen by night: the former ended up informing the latter, Anthony suggests. “The character of Lily is definitely referencing some of those mums from troubled backgrounds, doing whatever it took to survive, that kind of thing,” he says.

Her sense of humour was, well, savage: “scurrilous and filthy and real”, as Graham Norton, one of The Life and Death of Lily Savage’s many celebrity talking heads, puts it. As the Eighties went on, Lily landed a residency at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, and became a fixture on the capital’s drag scene.

“[Lily] got away with things that everyone else would like to say but didn’t dare,” Gaby Roslin tells me.

The presenter, who also features in the documentary, was a good friend of O’Grady, and met him while working on The Big Breakfast in the Nineties. But, she says, the act was “never cruel” – O’Grady (or “Sav”, as Roslin still calls him) didn’t punch down. “Lily could say things and could be really cutting. But there was nothing unkind about Paul.”

And Lily had plenty to rail against. “There was a miners’ strike going on, there was Section 28 going on for the gay community,” Anthony says. “There was a lot to be cross about, and [O’Grady] was very angry about a lot of stuff.”

The Aids crisis would also cast a shadow. “I was either at hospitals or at funerals for two or three years,” O’Grady says in the film, while friends recall how he would visit friends in character as Lily, doing ward rounds, asking patients whether they wanted “red or white [wine]” from the trolley.

Family ties: Paul O’Grady with his daughter Sharyn (Olga TV/Silver Star Productions)

Anecdotes like these mean that, even in these sadder moments, The Life and Death of Lily Savage is filled with colour. And the documentary has an especially personal dimension thanks to the involvement of O’Grady’s daughter Sharyn Mousley, who had never previously spoken about her father on camera.

Her mother Diane was a friend and colleague of O’Grady, who was just 18 when Mousley was born; “People might wonder how a gay man managed to father a daughter,” he later joked, “but I was a highly promiscuous teenager.”

Anthony went to visit Mousley during the research process. “We really got on,” he tells me. “Then I plucked up the courage to ask her, ‘Look, do you think you might ever actually talk to us and be in the programme?’ And she said yes, which was great, and I think it really does make all the difference [to the film]”.

Her stories are a riot, from the time O’Grady turned up and started breathing fire at her seventh birthday party, to her memories of going to the shops to pick up a few packs of tights for her dad (“I’d be like, ‘Have you got tan and black?’”).

The Nineties saw Lily break into the mainstream, earning a Perrier Award nomination at the Edinburgh Fringe and landing a spot as an interviewer on The Big Breakfast. “Nobody batted an eyelid that there was a drag queen on breakfast telly, and so nobody should,” Roslin says.

“That was before its time. It was just completely normal. I can’t remember anybody coming up to me and saying ‘What is a drag queen doing on TV?’” The early starts, though, didn’t necessarily suit O’Grady.

“There was a lot of: ‘Gab, Gab, Gab, oh my God, what time is it?’” Roslin laughs, temporarily adopting a gruff Scouse accent (O’Grady’s fondness for a good old moan becomes a running joke in the documentary).

Nobody batted an eyelid that there was a drag queen on breakfast telly

Gaby Roslin

“I’m like a bouncing child when I get up early, and he’d be like, ‘Oh, shut up Gaby,’” she adds. “But I think that’s why we got on so well – I could take the piss out of him too.” And his kindness shines through in another story that Roslin tells.

“When my mum died [in 1997], he rang me every afternoon for two weeks,” she says. “It was in the days of answer phones, and he left a message every day.

He’d say ‘don’t pick up the phone’ and he’d tell me a joke or he’d tell me about his day. And at the end of the two weeks, he said ‘Now, if you feel like talking, you know where I am.’ That’s a true friend.”

By the early Noughties, Lily was a TV fixture, presiding over primetime shows such as Blankety Blank – and there are plenty of anarchic outtakes from the game show featured in the documentary.

But in 2004, O’Grady suddenly decided to retire his alter ego: her last appearance would be an interview on Parkinson. O’Grady had got fed up with the dressing up, plus, Anthony suggests, Lily was a character who was “very much of her moment”, a product of the Eighties and Nineties.

O’Grady also wanted to carve out a TV career as Paul O’Grady. “I think the film is partly about this idea that sometimes you have to be somebody else first, in order to be yourself,” Anthony suggests. “He needed Lily in order to get to a point where he could actually just be himself [on TV].”

Bold: O’Grady retired the character that made him famous at the height of her popularity (Olga TV/Silver Star Productions)

The public, of course, warmed to the real O’Grady pretty quickly. He’d go on to helm chat shows on ITV and Channel 4, highlight the work of Battersea Dogs & Cats Home in For the Love of Dogs, and explore the world on travel programmes (a priceless clip from one of them appears in the documentary, showing O’Grady moaning about having spent an hour trying to find the toilet in his massive hotel room).

“It’s extraordinary that he managed to have these two obviously linked but quite separate careers,” says Anthony. “He risked everything, didn’t really care what the consequences were [when he] gave up Lily, then had an even more successful career after that.”

Even as he was embraced by the establishment – in 2022 he filmed a special episode of For The Love of Dogs with Queen Camilla – he remained “a rebel at heart”, Anthony suggests, and it was important for the film to reflect that.

“The reason why we put the rabble-rousing clips from Paul O’Grady Live [where he rails against the Conservatives] is that that bit of Paul was still in there somewhere. He could go and do dog shows, meet Camilla, be given an OBE and all that kind of thing, but still be the same person, more or less.”

Different chapter: O’Grady filmed a special episode of ‘For The Love of Dogs’ with Queen Camilla (Getty)

Anthony hopes that, by charting Lily and O’Grady’s rise and rise, his documentary will show “the real progress that we’ve made in this country in terms of visibility of LGBTQ people and understanding of gay rights”.

TV stars like O’Grady, he adds, helped to “normalise a lot of the acceptance that we all take for granted now”, and his remarkable career also tells “a more serious story” about “how far gay people have come in the last 40 years, from pariah [status] to completely and totally mainstream. It’s quite an amazing transformation just in one generation, really”. Not bad for a “blonde bombsite” from Birkenhead.

‘The Life and Death of Lily Savage’ is on ITV1 and ITVX on Friday 29 March at 9pm